Scientists say they have used the gene editing tool Crispr-Cas9 inside a person’s body for the first time, a new development in efforts to operate on DNA to treat diseases.

A patient recently underwent a procedure at the Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland for an inherited form of blindness, the companies that make the treatment announced on Wednesday. They would not give details on the patient or when the surgery occurred.

It may take up to a month to see whether the procedure worked to restore vision. If the first few attempts seem safe, doctors plan to test the technique on 18 children and adults.

“We literally have the potential to take people who are essentially blind and make them see,” said Charles Albright, the chief scientific officer at Editas Medicine, a Massachusetts-based company developing the treatment with Dublin-based Allergan. “We think it could open up a whole new set of medicines to go in and change your DNA.”

Dr Jason Comander, an eye surgeon at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston, another hospital that plans to enrol patients in the study, said it marked “a new era in medicine” using a technology that “makes editing DNA much easier and much more effective”.

Doctors first tried in-the-body gene editing in 2017 for a different inherited disease using a tool known as zinc fingers. Many scientists believe Crispr is a much better tool for locating and cutting DNA at a specific spot, and interest in the new research is very high.

The people in this study have Leber congenital amaurosis, caused by a gene mutation that keeps the body from making a protein needed to convert light into signals to the brain. They’re often born with little vision and can lose even that within a few years.

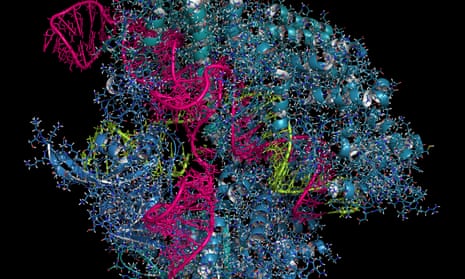

Scientists cannot treat it with standard gene therapy – supplying a replacement gene – because the one needed is too big to fit inside the disabled viruses that are used to ferry it into cells. So they are aiming to edit or delete the mutation by making two cuts on either side of it. The hope is that the ends of DNA will reconnect and allow the gene to work as it should.

During an hour-long surgery under general anaesthesia, doctors drip three drops of fluid containing the gene editing machinery through a tube the width of a hair to just beneath the retina, the lining at the back of the eye that contains the light-sensing cells.

“Once the cell is edited, it’s permanent and that cell will persist hopefully for the life of the patient,” because these cells don’t divide, said Dr Eric Pierce at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, a study leader not involved in the first case.

Doctors think they need to fix between one-tenth and one-third of the cells to restore vision. In animal tests, scientists were able to correct half of the cells with the treatment, Albright said.

The eye surgery poses little risk, doctors say. Infections and bleeding are relatively rare complications.

One of the biggest potential risks from gene editing is that Crispr could make unintended changes in other genes, but Pierce said the companies had done a lot to minimise that and to ensure that the treatment cuts only where it’s intended to.

Some independent experts were optimistic about the new study. Dr Jean Bennett, a University of Pennsylvania researcher, said: “The gene editing approach is really exciting. We need technology that will be able to deal with problems like these large genes.”

She said she had received three calls in one day from families seeking solutions to inherited blindness. “It’s a terrible disease,” she said. “Right now they have nothing.”

Dr Kiran Musunuru, another gene editing expert at the University of Pennsylvania, said the treatment seemed likely to work, based on tests in human tissue, mice and monkeys. The gene editing tool stays in the eye and does not travel to other parts of the body, so “if something goes wrong, the chance of harm is very small,” he said. “It makes for a good first step for doing gene editing in the body.”

The study has the approval of government regulators, unlike a Chinese scientist’s work that brought international scorn in 2018. He Jiankui used Crispr to edit embryos at the time of conception to try to make them resistant to infection with the Aids virus. Changes to embryos’ DNA can pass to future generations, unlike the work being done now in adults to treat diseases.