As America inches towards a potential trade war over steel prices can Donald Trump hear whispering voices? Alone in the Oval Office in the wee dark hours, illuminated by the glow of his Twitter app, does he feel the sudden chill flowing from those freshly hung gold drapes? It is the shades of Smoot and Hawley.

Willis Hawley and Reed Smoot have haunted Congress since the 1930s when they were the architects of the Smoot-Hawley tariff bill, among the most decried pieces of legislation in US history and a bill blamed by some for not only for triggering the Great Depression but also contributing to the start of the second world war.

Pilloried even in their own time, their bloodied names have been brought out like Jacob Marley’s ghost every time America has taken a protectionist turn on trade policy. And America has certainly taken a protectionist turn.

Successful presidents including Barack Obama and Bill Clinton have campaigned on the perils of free trade only to drop the rhetoric once installed in the White House. Trump called Mexicans “rapists” on the campaign trail. And China? “There are people who wish I wouldn’t refer to China as our enemy. But that’s exactly what they are,” Trump said.

As commander-in-chief he has shown no signs of softening and this week took major action announcing steel imports would face a 25% tariff and aluminium 10%.

Canada and the EU said they would bring forward their own countermeasures. Mexico, China and Brazil have also said they are considering retaliatory steps.

Trump doesn’t seem worried. “Trade wars are good,” he tweeted even as the usually friendly Wall Street Journal thundered that “Trump’s tariff folly” was the “biggest policy blunder of his Presidency”.

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 2, 2018

It is not his first protectionist move. In his first days in office the president has vetoed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the biggest trade deal in a generation, said he will review the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), a deal he has called “the worst in history”, and had his visit with Mexico’s president cancelled over his plans to make them pay for a border wall.

Free traders may have become complacent after hearing tough talk on trade from so many presidential candidates on the campaign trail only to watch them furiously back-pedal when they get into office, said Dartmouth professor and trade expert Douglas Irwin. “Unfortunately that pattern may have been broken,” he says. “It looks like we have to take Trump literally and seriously about his threats on trade.”

Not since Herbert Hoover has a US president been so down on free trade. And Hoover was the man who signed off on Smoot and Hawley’s bill.

Hawley, an Oregon congressman and a professor of history and economics, became a stock figure in the textbooks of his successors thanks to his partnership with the lean, patrician figure of Senator Reed Smoot, a Mormon apostle known as the “sugar senator” for his protectionist stance towards Utah’s sugar beet industry.

Before he was shackled to Hawley for eternity Smoot was more famous for his Mormonism and his abhorrence of bawdy books, a disgust that inspired the immortal headline “Smoot Smites Smut” after he attacked the importation of Lady’s Chatterley’s Lover, Robert Burns’ more risqué poems and similar texts as “worse than opium … I would rather have a child of mine use opium than read these books.”

But it was imports of another kind that secured Smoot and Hawley’s place in infamy.

The US economy was doing well in the 1920s as the consumer society was being born to the sound of jazz. The Tariff Act began life largely as a politically motivated response to appease the agricultural lobby that had fallen behind as American workers, and money, consolidated in the cities.

Foreign demand for US produce had soared during the first world war, and farm prices doubled between 1915 and 1918. A wave of land speculation followed and farmers took on debt as they looked to expand production. By the early 1920s farmers had found themselves heavily in debt and squeezed by tightening monetary policy and an unexpected collapse in commodity prices.

Nearly a quarter of the American labor force was then employed on the land, and Congress could not ignore heartland America. Cheap foreign imports and their toll on the domestic market became a hot issue in the 1928 election. Even bananas weren’t safe. Irwin quotes one critic in his book Peddling Protectionism: Smoot Hawley and the Great Depression: “The enormous imports of cheap bananas into the United States tend to curtail the domestic consumption of fresh fruits produced in the United States.”

Republicans called protective tariffs “essential for the continued prosperity of the country” and Hoover, who said agriculture was “the most urgent economic problem” facing the nation, said “an adequate tariff is the foundation of farm relief”.

Hoover won in a landslide against Albert E Smith, an out-of-touch New Yorker who didn’t appeal to middle America, and soon after promised to pass “limited” tariff reforms.

Hawley started the bill but with Smoot behind him it metastasized as lobby groups shoehorned their products into the bill, eventually proposing higher tariffs on more than 20,000 imported goods.

Siren voices warned of dire consequences. Henry Ford reportedly told Hoover the bill was “an economic stupidity”.

Critics of the tariffs were being aided and abetted by “internationalists” willing to “betray American interests”, said Smoot. Reports claiming the bill would harm the US economy were decried as fake news. Republican Frank Crowther, dismissed press criticism as “demagoguery and untruth, scandalous untruth”.

In October 1929 as the Senate debated the tariff bill the stock market crashed. When the bill finally made it to Hoover’s desk in June 1930 it had morphed from his original “limited” plan to the “highest rates ever known”, according to a New York Times editorial.

The extent to which Smoot and Hawley were to blame for the coming Great Depression is still a matter of debate. “Ask a thousand economists and you will get a thousand and five answers,” said Charles Geisst, professor of economics at Manhattan College and author of Wall Street: A History.

What is apparent is that the bill sparked international outrage and a backlash. Canada and Europe reacted with a wave of protectionist tariffs that deepened a global depression that presaged the rise of Hitler and the second world war. A myriad other factors contributed to the Depression, and to the second world war, but inarguably one consequence of Smoot-Hawley in the US was that never again would a sitting US president be so avowedly anti-trade. Until today.

Franklin D Roosevelt swept into power in 1933 and for the first time the president was granted the authority to undertake trade negotiations to reduce foreign barriers on US exports in exchange for lower US tariffs. The backlash against Smoot and Hawley continued to the present day. The average tariff on dutiable imports was 45% in 1930; by 2010 it was 5%.

The lessons of Smoot-Hawley used to be taught in high schools, said Geisst. Presidents from Lyndon Johnson to Ronald Reagan have enlisted the unhappy duo when facing off with free trade critics. “I have been around long enough to remember that when we did that once before in this century, something called Smoot-Hawley, we lived through a nightmare,” Reagan, who came of age during the Great Depression, said in 1984.

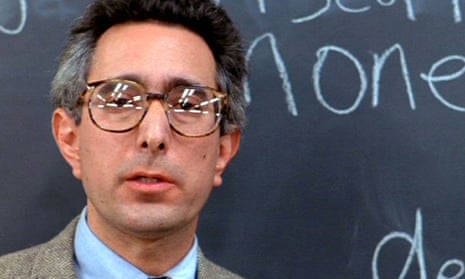

They even got a mention in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off when actor Ben Stein’s teacher bores his class with it. “I don’t think the current generation are taught it. It’s in the past and we are more interested in the future,” said Geisst.

But that might be about to change. “The main lesson is that you have to worry about what other countries do. Countries will retaliate,” said Irwin. “When Congress was considering Smoot-Hawley in the 1930s they didn’t consider what other countries might do in reaction. They thought other countries would remain passive. But other countries don’t remain passive.”

The consequences of a trade war today are far worse than in the 1930s. Exports of goods and services account for about 13% of US gross domestic product (GDP) – the broadest measure of an economy. It was roughly 5% back in 1920.

“The US is much more engaged in trade, it’s much more a part of the fabric of the country, than it was in the 1920s and 1930s. That means the ripple effects are widespread. Many more industries will be hit by it and the scope for foreign retaliation, which in the case of Smoot-Hawley was quite limited, is going to be much more widespread if a trade war was to start,” said Irwin.

“When you start talking about withdrawing from trade agreements or imposing tariffs of 35%, if you are doing that as a protectionist measure, that would be blowing up the system.”

That the promise of “blowing up the system” got Trump elected may be why the ghosts of Smoot and Hawley are once again walking the halls of Congress.